The History of Modern Dogs

In zoological terms, dogs belong to the:

- Class — Mammalia (mammals)

- Order — Carnivora (meat-eaters)

- Family — Canidae (dog family)

- Genera — Canus (all canines)

- Species — Familiaris (modern dog)

According to historians the order Carnivora (meat-eaters) includes our modern-day dogs and cats along with other species that rely on meat as a primary source of nutrition.

Scientific evidence points to the fact that all dogs — wild and domestic, extinct and living — belong to the family Canidae. Assuming a constant rate of sequence evolution, the dog family Canidae diverged from other carnivore families approximately 50 million years ago, near the time when Canids first appeared in fossil records. The family Canidae is a diverse group of 35 species belonging to three main groups:

Hesperocyon

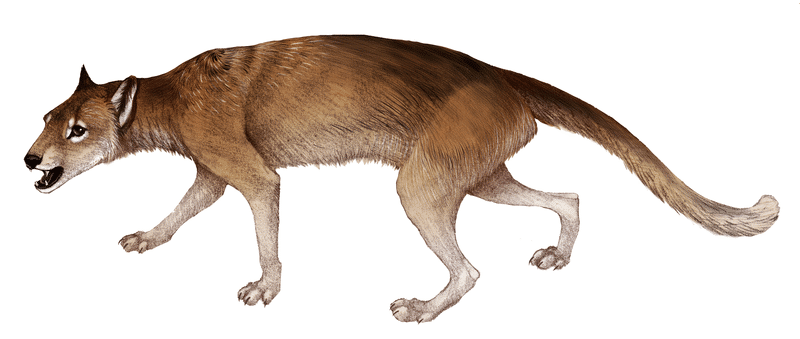

The first group evolved in North America about 40 million years ago. Fossil evidence tells us that these first dogs looked like a cross between a weasel and a fox. The name Hesperocyon means “western dog.” The Hesperocyonines became extinct about 15 million years ago.

Borophagines

The second group, the Borophagines, began flourishing about 34 million years ago and was a larger hyena-like animal with huge jaw muscles and sturdy teeth. They became extinct about 2.5 million years ago.

Canines

The third group, the Canines includes the wolf and all living species of dogs. This group occurred only in North America until about 7 million years ago when some species crossed a land bridge to Asia.

An Evolutionary Tail – From Wolf to Woof

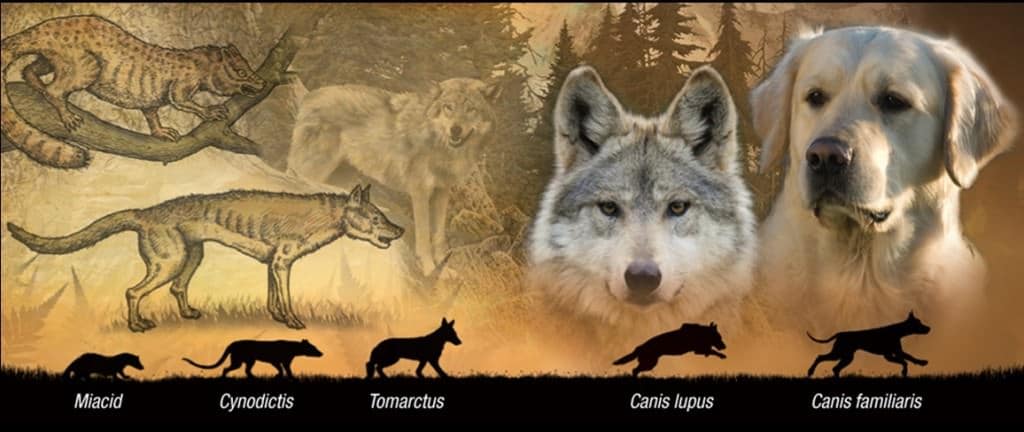

The dog, Canis familiaris, is a direct descendent of the gray wolf, Canis lupus. In other words, dogs are domesticated wolves that are primarily smaller and better behaved.

How and when this domestication happened has been a matter of speculation. It was thought until very recently that dogs were wild until about 12,000 years ago. However, DNA analysis published in 1997 suggests a date of about 130,000 years ago for the transformation of wolves to dogs. This means that wolves began to adapt to human society long before humans settled down and began practicing agriculture.

This earlier timing casts doubt on the long-held myth that humans domesticated dogs to serve as guards or companions to assist them. Rather, some experts say dogs may have exploited a niche they discovered in early human society and got humans to feed them and take them in out of the cold.

Based on the molecular genetic analysis of Mitochondrial DNA between domestic dogs and wolves, there is direct evidence that the genetic ancestor of the domestic dog is the grey wolf (Canis lupus). The domestic dog differs from the gray wolf by at most 0.2% in their mitochondrial DNA sequence. In comparison, the gray wolf differs from its closest wild relative, the coyote, by about 4%.

Professor Robert Wayne stated that dogs are gray wolves, despite their diversity in size and population, and that the wide variation in their adult morphology is probably the result of simple changes in the developmental rates and timing. Recently, Wayne and his colleagues carried out an extensive survey of DNA sequence polymorphisms among domestic dogs and wild wolves. They concluded that:

- Domestic dogs were most probably derived from two wolf populations separated geographically in the north and south.

- Dogs had multiple origins, based on extensive polymorphisms shown in dog populations

- Extensive interbreeding occurred in the ancestral stocks of domestic dogs

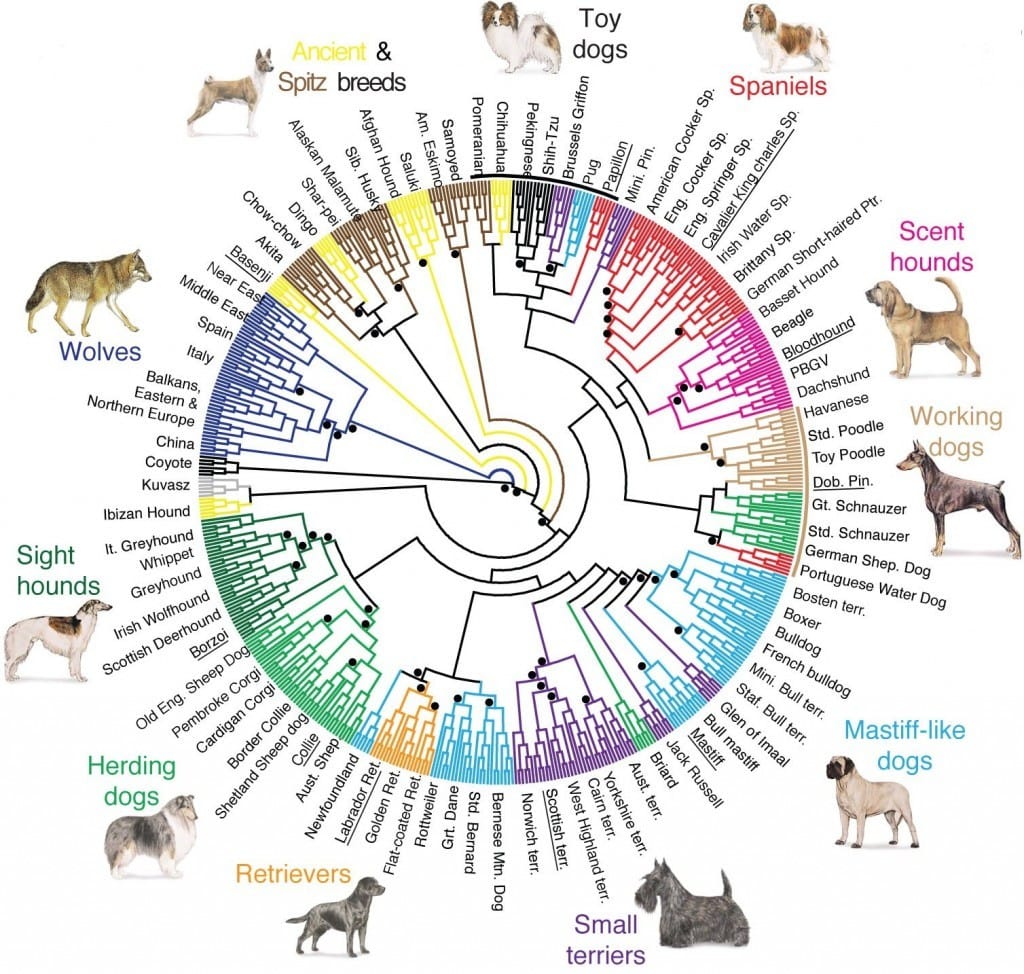

Dogs vary so greatly in their physical appearance today it is difficult to surmise that they all belong to the same species. The profusion of individual breeds — at least 400 around the globe — reflects years of selective interbreeding by humans resulting in the “artificial evolution” of dogs into many different breeds and types.

All domestic dogs, from the Chihuahua to St. Bernard, carry the same DNA patterns and thus belong to a single species. The only domestic dog that varies is the Arctic Elkhound, which appears to have evolved separately. A species is a group of individuals that can successfully reproduce with one another. A breed is a sub-group of domestic animals whose looks and behavior have been shaped by human selection. All breeds within a species can potentially reproduce with each other, but the distinctive features of breeds can be lost when one breed is crossed with another.

One consequence of interbreeding to create man-made purebreds, each with unique type and individual traits, is that over the years, many behavior and disease-causing genes have been introduced and concentrated in these breeds creating numerous canine health problems that still persist today.

The Canine Domestication Timeline

1 Million BC

The gray wolf family becomes the world’s largest canine group.

100,000 BC

Gray wolves and subspecies are spread across Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and America. Man begins selecting wolves for puppy characteristics as camp pets.

20,000 BC

Stone Age man breeds dogs for his own purposes. The oldest evidence is a 14,000-year-old jaw with teeth of modern dog configuration found in Iraq.

7,000 BC

Egyptians develop dogs from their regions of Tibet & China.

4500 BC

Fossils of the period are of pointer types, mastiffs, greyhounds, shepherds, and the wolf-like spitz.

3500 BC

Basic dog types reach Europe.

3,000 BC

A Prototype pointer skeleton found in England exhibits evidence of greyhound and mastiff characteristics. Modern hunting dogs will evolve from these prototypes called Canis familiaris intermedius.

2,000 BC

As the Neolithic period ends, most basic breeds are established.

23 – 79 AD

The Roman Pliny writes about hunters carrying dogs that stiffen and point their noses at game concealed in the undergrowth.

100 – 1500

Though there are few breeds in any one region, breeds and strains number into the thousands worldwide.

1800 – 1900

Distinctive breed separations and refinements advance rapidly through kennel clubs and knowledge of scientific animal breeding.

After wild dogs learned not to bite the hand that fed them,

French poodles weren’t far behind.

The History of Modern Cats

In zoological terms, cats belong to the:

- Class: Mammalia (hair covered animals that suckle their young with breast milk)

- Order: Carnivora (meat eaters)

- Family: Felidae (within this family there are three subdivisions – Genera)

- Genera:

- Panthera (cats that roar)

- Acinonyx (the Cheetah)

- Felis (all other “small” cats)

- Species: Domesticus (domestic cats)

Each Genus contains individual species. A species of cats is a group that normally breeds and produces fertile offspring. No one knows exactly when or how the cat first appeared on Earth. Most investigators agree, however, that the cat’s most ancient ancestor probably was a weasel-like animal called Miacis, which lived about 40 to 50 million years ago.

Miacis is believed by many to be the common ancestor of all land-dwelling carnivores, including dogs as well as cats. Perhaps best known of the prehistoric cats is Smilodon, the saber-toothed cat sometimes called a tiger. This formidable animal hunted throughout much of the world but, long ago became extinct.

General Characteristics of Cats

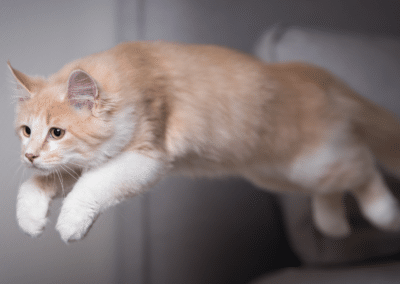

Cats have evolved as predatory hunting animals with great agility and keen senses – particularly hearing, sight, and smell. From only a few weeks of age, the kittens of all species of cat (including our domesticated varieties) show instinctive behavior typical of hunter-killers. They are extremely alert to sounds and movements, stalk, ambush, convert rigid stillness into rapid movements to pounce on their prey, and they demonstrate the typical biting and clawing actions needed to bring down and kill prey quickly.

All cats (except the lion and some feral domestic cat colonies) are solitary animals that hunt and fend for themselves. They only come into contact with members of the opposite sex during mating periods when the scent in female urine attracts males to her from a long distance. Cats are also very territorial and mark out the perimeter of their “homeland” with their urine.

In urban areas our domesticated cats still exhibit these behavioral traits, creating serious problems for male tomcats that inevitably fight with each other as they cross each other’s territories in search of females. Neutering can help to reduce the nuisance caused by calling and fighting cats, as well as reducing the number of unwanted litters.

Anatomical characteristics

There are several anatomical features such as a rounded head and a skeletal structure designed for agility, which suggests that all cats (domesticated or wild, large or small) have evolved from a common prehistoric ancestor.

Generally, male and female cats are very similar in appearance. The exceptions are adult male lions, which develop a mane. Usually, males are slightly bigger than females of the same species.

Cats have five toes on the front feet and four toes on the hind feet, although occasionally individuals are born with more toes (an inherited abnormality called polydactyly). Cats walk on their toes and have soft pads on the toes and feet which help to reduce sound when stalking, as well as protecting the underlying bones from concussion during running and jumping.

Cats have evolved with eyes that protrude forwards from the head giving them good forward and sideways vision. The retina at the back of the eye reflects light from an area called the tapetum lucidum, which consists of a high proportion of cells called “rods” that gives the cat excellent vision in poor light – a feature that helps them to hunt around dusk and dawn. Although the image they see is useful, it lacks fine detail so they may miss small objects. Cats do have cones in the retina for differentiating color – but their color vision is very poor compared to ours.

Cats have a dental profile typical of carnivores. They have four large canine teeth at the front of the mouth, which are used to grasp their prey and large molars including two carnassial teeth (one on the upper arcade of both sides of the mouth). These are used to gnaw and slice the meat into small pieces so that it can be swallowed.

It should be noted that all cats – including domesticated species – are obligate carnivores and they cannot survive without ingesting nutrients derived from other animals.

CATS MUST NEVER BE FED AN EXCLUSIVE VEGETARIAN RATION.

One genus of cat – the roaring cats (Panthera), which includes the lion, tiger, leopard, clouded leopard, snow leopard, and jaguar, has been so named based upon an anatomical difference in the hyoid bone apparatus. The hyoid lies at the base of the skull and connects it to the larynx. It is made partly of cartilage, which allows it to move freely and so gives the vocal cords the ability to make roaring sounds. In all other cats, the hyoid bone is completely ossified and rigid.

All cats have retractable claws except for the Cheetah – and for this reason, it is placed in its own genus – Acinonyx.

Cats have developed with a wide variety of coat colors and patterns. In wild cats, these have evolved as camouflage. It is not surprising therefore that the snow leopard should have a very pale, light, almost white coat – as it inhabits regions frequently covered in snow, whereas its counterpart the leopard has spots to help conceal it in forests. Tigers have stripes to conceal them in long grass; lions are tawny-brown to blend in with the savannah, and so on. Because coat color is a genetically inherited feature, breeders can influence this in their breeding.

DNA – Inheritance and Gene Sequencing

All cats have 38 chromosomes in each cell except for Ocelot’s and Geoffrey’s Cat, which only have 36 chromosomes.

A species of cat is a group that normally breeds and produces fertile offspring. However, under artificial conditions – such as captivity – it is possible to crossbreed different species and create variants:

- Leopards and lions have been crossed to create leopons

- Male lions and female tigers have been crossed to create ligers

- Male tigers and female lions have been crossed to create tigons

The offspring are usually sterile. An exception to this “rule” is that feral domestic cats have successfully bred in the wild with their wild counterparts.

The genetic transfer of material can explain the anatomical, behavioral, and other characteristics of modern-day cats from one generation to another, such as the principle of “survival of the fittest” and adaptation to the surrounding environments. Sometimes a desirable trait transmitted by a genetic sequence can be linked to an undesirable trait. The most notable example of this is a white hair coat. White cats are often born deaf, are also predisposed to develop hypersensitivity, and in some cases cancer of the earflaps (pinnae) when exposed to sunlight.

Laboratory sequencing of feline DNA (the feline genome) is currently being undertaken, and as a result, we shall discover more and more about the genetic component of inheritance in these species. This will not only help us to prevent and treat common diseases, but it will help us to piece together the evolutionary trail leading to modern-day cats.

Functional Characteristics

In addition to the behavioral characteristics of cats as predators, there are some interesting functional characteristics that are thought to reflect the cat’s origins as a desert-dwelling creature. One of these is the ability of cats kidneys to concentrate urine much more than other domesticated.

Cats also demonstrate some unique metabolic characteristics, which set them aside from other domesticated animals such as dogs. As a result, they have a specific nutritional requirement for taurine, preformed vitamin A and for the essential fatty acid, Linolenic acid.

Pictorial Artifacts and Written Records

Evidence of modern small cats is approximately 12 million years old. There is also evidence that three million years ago a wide variety of cats populated the entire world. Cat skeletons have been found in very early human settlements, but they are assumed by archaeologists to have been wild cats. The earliest true record of cat domestication comes from Ancient Egypt about 2000 years ago.

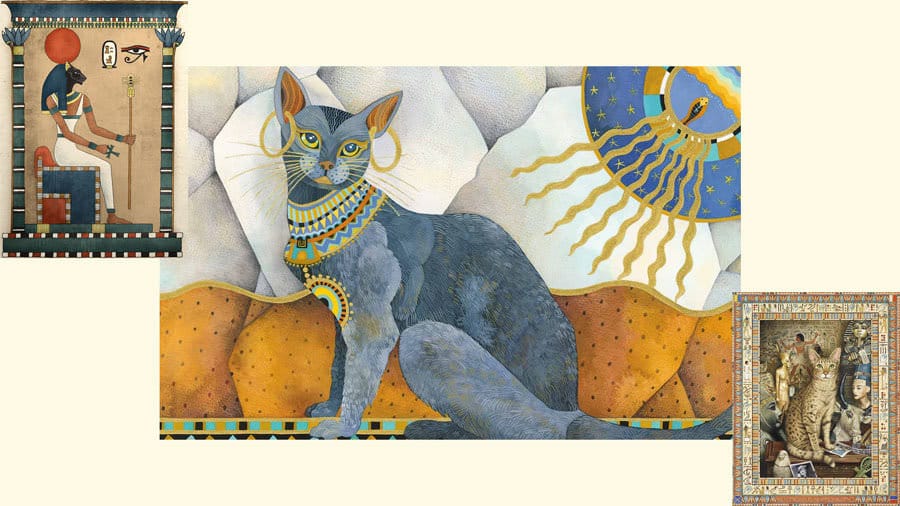

Paintings and inscriptions of cats from 2000BC in Egypt suggest that they were living with humans as domesticated animals at that time and later the cat became an important religious symbol, even being buried in their own cemeteries.

The photograph shows an Egyptian figure of a cat dating from about 900BC.

Naturally, humans would have selected cats with a docile nature and kept those that responded positively to human behavior. From North Africa, the domestication of cats spread through the Middle East, India, and China but human settlements in Europe didn’t have domesticated cats until the Romans introduced them much later.

Cats were kept on ships to control the rodent population and as a result, the seafaring explorers from Europe carried and introduced domesticated cats all over the world.

The Cat in History

Cats in the Ancient World

The first associations of cats with humans may have begun toward the end of the Stone Age. It took many centuries, however, for the cat to become established as a domestic animal. About 5,000 years ago, cats were accepted members of the households of Egypt. Many of the breeds we now know have evolved from these ancient cats. The Egyptians used the cat to hunt fish and birds as well as to destroy the rats and mice that infested the grain stocks along the Nile. The cat was considered so valuable that laws protected it, and eventually a cult of cat worship developed that lasted for more than 2,000 years. The cat goddess Bastet became one of the most sacred of all figures of worship. She was represented with the head of a cat. Soon all cats became sacred to the Egyptians, and all were well cared for. After a cat’s death, its body was mummified and buried in a special cemetery. One cemetery found in the 1800s contained the preserved bodies of more than 300,000 cats.

The Egyptians had strict laws prohibiting the export of cats. However, because cats were valued in other parts of the world for their rat-catching prowess, they were taken by the Greeks and Romans to most parts of Europe. Domestic cats were also found in India, China, and Japan where they were prized as pets as well as rodent catchers.

Cats in the Medieval World

The fate of the cat underwent a radical change in Europe during the middle ages. It became an object of superstitions and was associated with evil. The cat was believed to be endowed with powers of black magic — an associate of witches and perhaps the embodiment of the devil. Persons who kept cats were suspected of wickedness and were often put to death along with their cats. Cats were hunted, tortured, and sacrificed. On religious feast days, large numbers of cats were sometimes burned alive as part of the celebrations. Live cats were sealed inside the walls of houses and other buildings as they were being constructed, in the belief that this would bring good luck. As the cat population dwindled, the disease-carrying rat population increased a factor that contributed greatly to the spread of plagues and other epidemics throughout Europe.

By the 17th century, the cat had begun to regain its former place as a companion to people and a controller of rodents. Cardinal Richelieu, in France, was noted for his love of cats. Many writers, particularly in France and England, began to keep cats as pets and to write of their good qualities. It became fashionable to own and breed cats, especially the longhaired varieties. By the late 1800s, cat shows were being held in England and the United States, and cat fanciers’ organizations were established. Many of the superstitions that arose during the period of cat persecution, however, are still evident today in the form of such sayings as “A black cat crossing your path brings bad luck.”

Cats in the Arts

The cat has been a favorite subject of artists and writers for centuries. Perhaps best known of all artistic representations are those of the Egyptian cat goddess Bastet. Ancient sculptures and drawings of her image with the head of a cat have been found in many places in the Nile Valley. Japanese artists excelled in portraying the cat. Some of the drawings were so realistic that in ancient times they were thought to be magic. People believed that if the drawings themselves were hung in homes and in temples they kept rats and mice away. Among the most charming of these Japanese cats is Maneki-Neko, a small cat believed to ensure happiness and good luck. Japanese Buddhists venerate cats after death, and the temple of Go-To-Ku-Ji in Tokyo is dedicated to them.

Vested priests serve the temple and intone chants for feline souls. Crowded into the temple are sculptures, paintings, and relief carvings of cats. In each, the cat has a paw raised as if in greeting, the classical pose of Maneki-Neko.

Cats have been portrayed in the works of many great artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Durer, Paul Gauguin, Theodore Gericault, William Hogarth, Edouard Manet, and Pablo Picasso. Probably the best-known cat in the world is Felix the Cat, the star of animated cartoon films. Other famous cartoon cats include Krazy Kat and Tom (of Tom and Jerry), both of which had mice for companions. Musicians such as Gioacchino Rossini and Maurice Ravel have also paid homage to the cat in compositions.

Fables and tales about cats are part of the culture of most people. Versions of the Puss in Boots fable occur in almost every language, and the tale of Dick Whittington and his cat is well known. The personality and beauty of cats have inspired many poets. Readers of all ages enjoy books about cats.

Thank you for this informative article. I am a high school science teacher and have my students doing research to compare different animals and this is a great resource. I appreciate this well designed comparison.